The Life-Cycle of the Angels

Many tarot books describe the first 21 cards of the deck following the Fool card—otherwise known as the major arcana—as the "Fool's Journey", in which the Fool progresses through 21 stages of existence. In the Cheimonette Tarot, one could just as easily call this the Angels' Journey. The Fool transforms into the Angel in two ways, both of which are represented in the narrative sequence of the major arcana.

The Biological Life Cycle

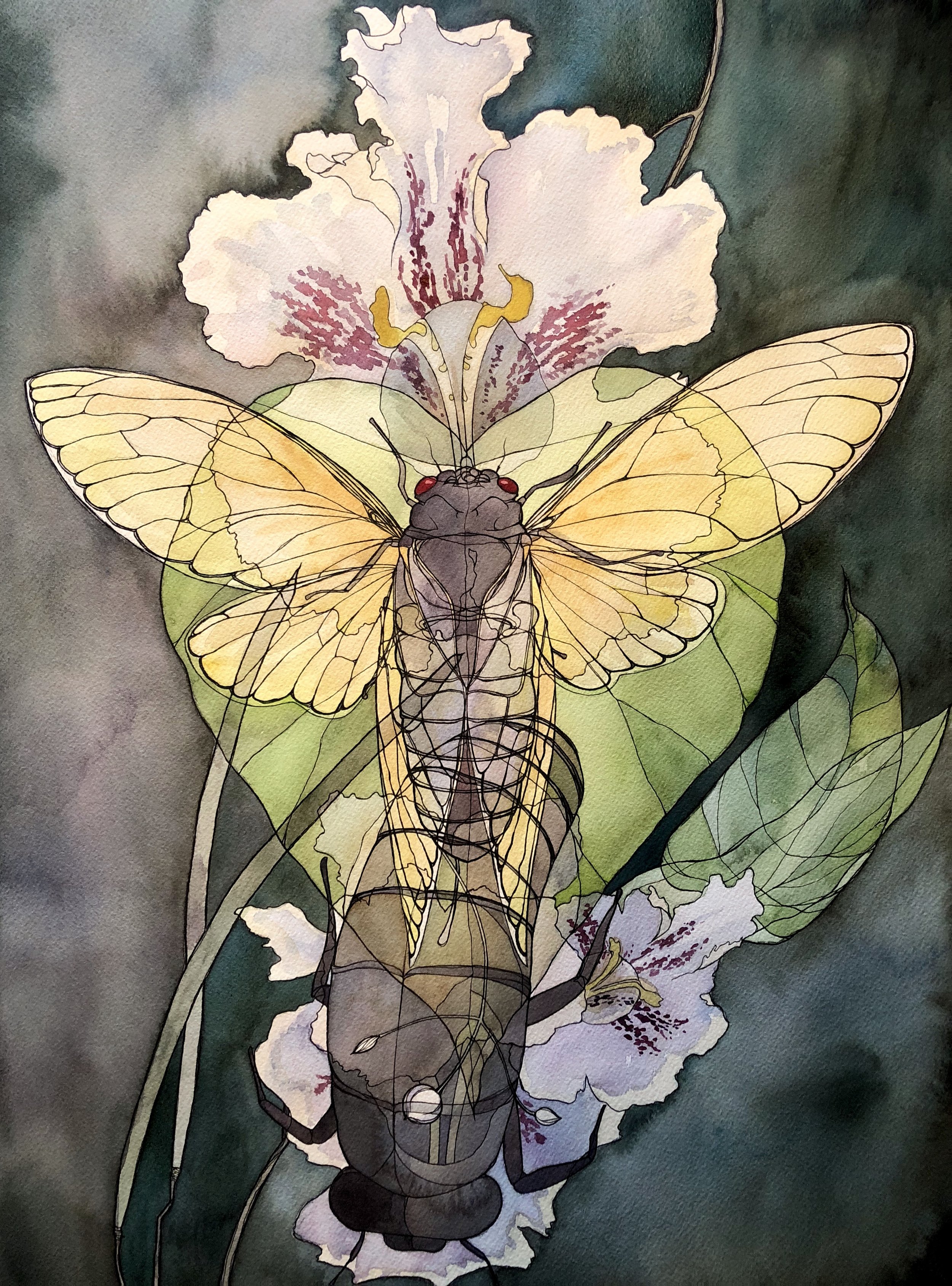

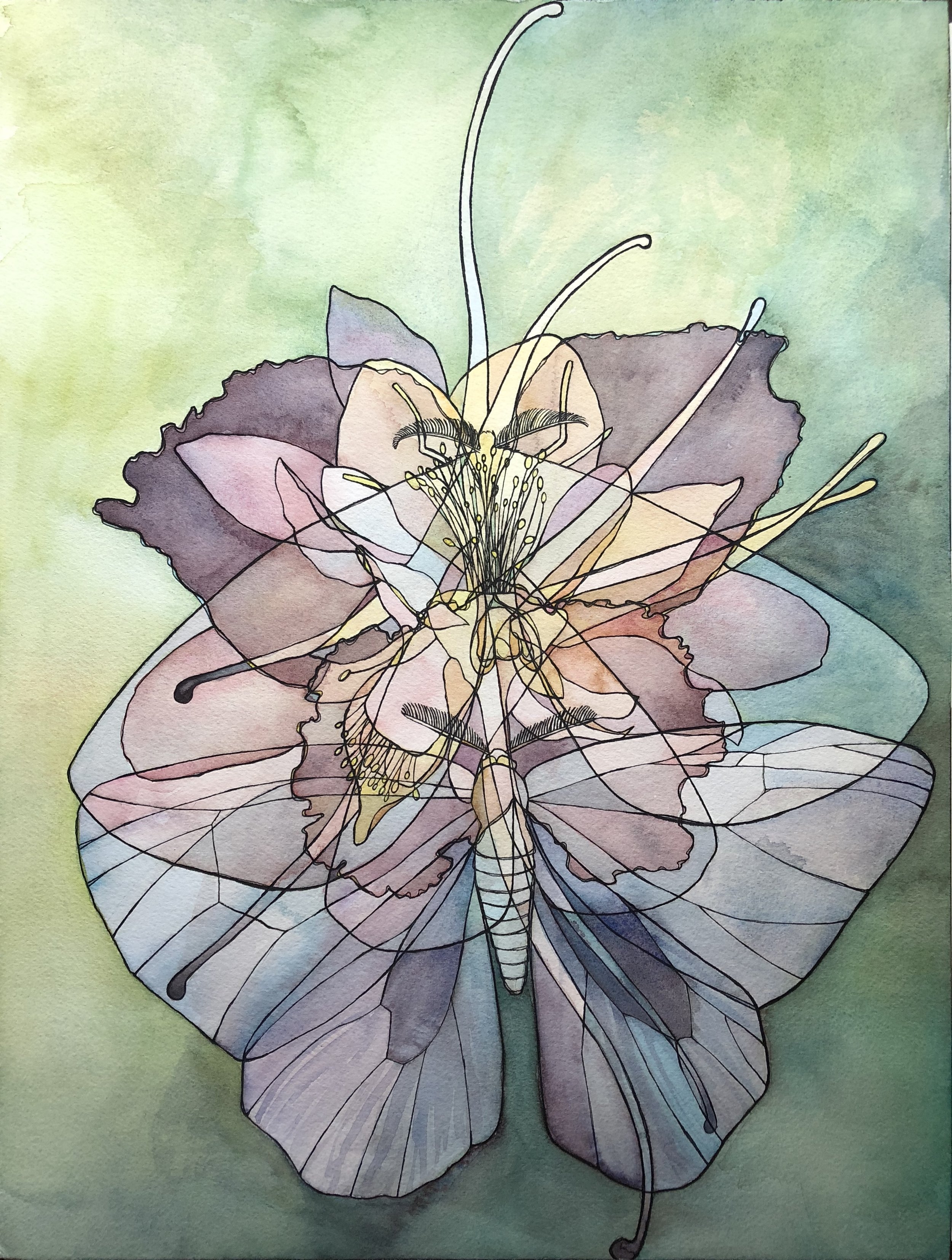

If you have been following my recent work, you've seen my recent botanical/ entomological paintings, which experiment with different pair relationships: morphological (maple tree samaras resemble the wings of lacewings), geographic (the Southern Catalpa and the tredecassini 13-year cicada have intersecting habitats), morphological (maple tree samaras resemble the wings of lacewings), and chromatic (the petals of white columbines have the same hue—even down to their rose-mauve shadows—as the wings of the white moth). As I learned more about each of these species, I became familiar with their life cycles, which are often incredibly detailed and bizarre. For example, periodic cicadas remain underground in their larval stage for the majority of their lives, progressing through several morphological stages as they feed off the sap from tree roots. At last, they "hatch" out of their hardened larval bodies into the large, singing imago (the winged adult) at which point they mate, reproduce, and die over a span of only a few weeks.

Magicicada tredecassini x Catalpa bignonioides, (2018). Ink and watercolor on paper.

Acer circinatum x Chrysopa perla (2018). Ink and watercolor on paper.

Aquilegia vulgaris, Iris sibirica x Haploa reversa (2018). Ink and watercolor on paper.

The Cheimonette Angels

The 21 cards of the major arcana organize different primary concepts of human experience. In the Cheimonette Tarot, the Fool (card 0) takes two overlapping routes to become the Angel (card XX): in one sequence, the Fool simply grows wings (card XII: the Hanged Man) and finally reveals the Angel nature it had all along (card XX: the Angel); in the other sequence, twin angels divide (card VI: Love), separate (card X: the Wheel) and converge (card XV: the Devil), and finally combine to become a single Angel (card XX), by appropriating the human qualities of the Fool.

The Fool (2002). Ink on paper.

These two parallel life cycles of the Fool/Angel can be thought of as interrelated, symbiotic life cycles of different biological species: sometimes mutually beneficial or harmful, sometimes competitive, sometimes parasitic, sometimes merely commensal. The two angels in Love (VI) are locked in a shared gaze of mutual support, trust, and safety: the perfect foundation for great freedom, experience, and exploration. In the Wheel (X), the angels have separated to form two independent bodies, working together to turn the wheel of time, dreaming their private dreams. In the Devil (XV), separation has become painful and the angels are reuniting catastrophically, seemingly in the act of annihilating each other. Only by becoming human can they be whole again, and they at last take on the animal characteristics of the Fool (its two tails), and resurrect as a single being, with the flower of immortality from the Tree of Life growing from its body, and the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge for a heart.

VI: Love (2003). Ink, watercolor, and colored pencil on paper.

X: The Wheel (2003). Ink and watercolor on paper.

XV: The Devil (2003). Ink, watercolor, and colored pencil on paper.

The other life cycle is simpler and gentler. It represents not the fall of a God, but the apotheosis of a mortal. Even though the Fool and the twin angels have different characteristics (the Fool has its tails, and the angels have their wings), they are arrestingly similar creatures: bald as an infant, androgynous, and seemingly sexless. This insight is personified by the Hanged Man (a card I should have renamed as gender neutral), hung by its own tails in a window of one of the Moon towers (which appear in both the Priestess and Moon cards). The Fool in the Hanged Man is clearly not compelled into its position: as a symbol of its freedom, it holds an unattached chain between its hands as a plumb weight. Out of its back grows incipient wings. It is passively waiting for its transformation to occur, suspended between the strange world within the Moon tower and the outer world occupied by us, the observers. Its eyes are open—which shows that waiting is perhaps not so passive as it might seem. It believes in its own potential for divinity. In the Angel card, we can see that the Fool's conviction was justified.

XII: The Hanged Man (2003). Ink, watercolor, and colored pencil on paper.

XX: The Angel (2004). Ink and watercolor on paper.

Plants and animals tend to have precisely as much as they need—and no more—to survive. If their lives are hard, they usually have the ability to endure those hardships. Animals are exactly as intelligent as they need to be, and so are we. Our own phases of existence are less apparently intricate than those of the 13-year cicada, but they are profoundly detailed nevertheless. The world we live in today is both of our own creation as well as far beyond our control. We experience reality as a web of probabilities: a fine mesh made from our own sensory experiences and from trusted authorities we use as outside sources of information.

But I believe that these probabilities rest on a set of core beliefs. Whether those beliefs are religious, scientific, philosophical, or emotional in character is of little importance. What is important is that there is a fundamental particle, somewhere, in all of us, that will bear no division, no scrutiny. Our blind spot.

"If this is not true, then nothing is true."

Not all of us must reach that part of our life cycle where we are called upon by circumstances to shatter our fundamental beliefs. When we are, we often become even more hard and immovable, so that our shells may be the easier to shatter, our hearts more easily broken. To allow the possibility that the imago, winged and singing, may emerge from the ruins of truth.