Bridges and Tunnels: artist statement manifesto, or why I'm not good at The News

Lately, I've been feeling dragged along by The News and its inevitable conclusions, into a world that I don't really want to live in. The news is full of cruelty and violence. Injustice seems as immovable as stone. Marginalized people (and, to a lesser extent, all of us) continue to be crushed by the social systems that we call home. And these things are true. We know it.

I don't really have much to say about The News.

Honestly, my voice isn't really all that important, and I want to make room for those voices that are. I am and have always been fixed within my own personal sphere of influence, unable to evaluate or even conceptualize human civilization at large: "Capital-P People", I call it. It's not for want of trying, either.

And I've always privately disagreed with the conclusions that revolution tends to draw.

The notion that human nature is inherently evil and that the world ought to die seems as plausible as not, but the thought is as meaningless to me as the idea that human nature is inherently good.

What, after all, can either conviction mean?

Whether or not we as a species are positive forces in the world (probably not), whether or not we are currently making a world we can survive in (almost certainly not), and whether or not the rest of the universe would be better off without us (who knows?) ...well, here we are anyway. So now what?

Many of my friends feel angry at the world much of the time, but I don't feel angry. All I seem to be able to feel is heartbroken. Over and over.

Maybe that sounds discouraging, or intolerably painful, or somehow less motivating than anger, but it isn't. If anything, it gives me hope. It's the one feeling I have that reaches beyond my sphere of influence into the world of strangers.

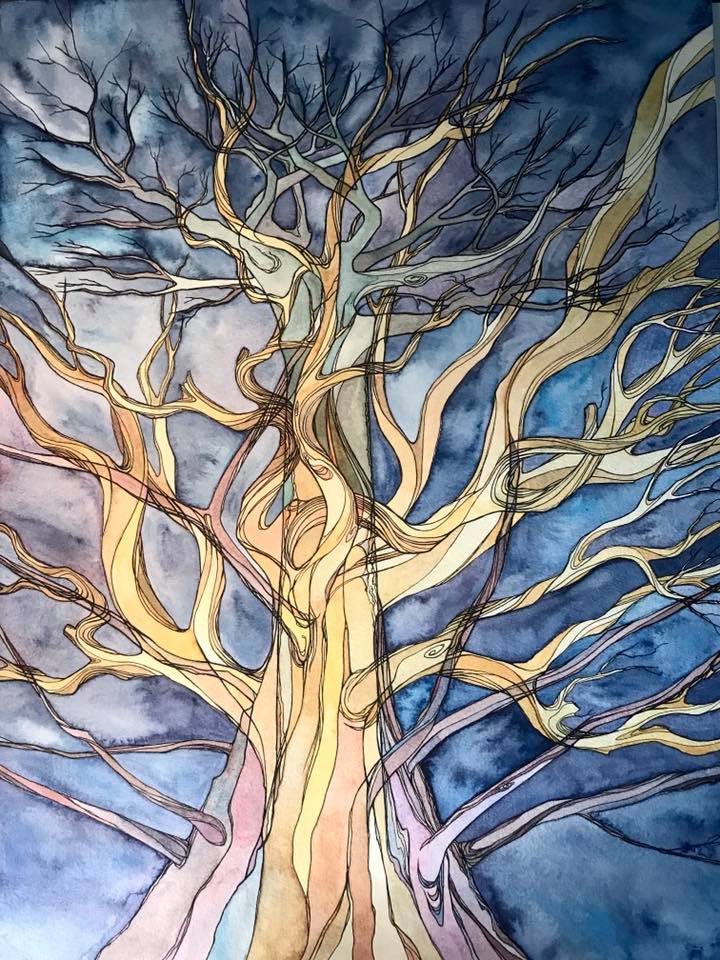

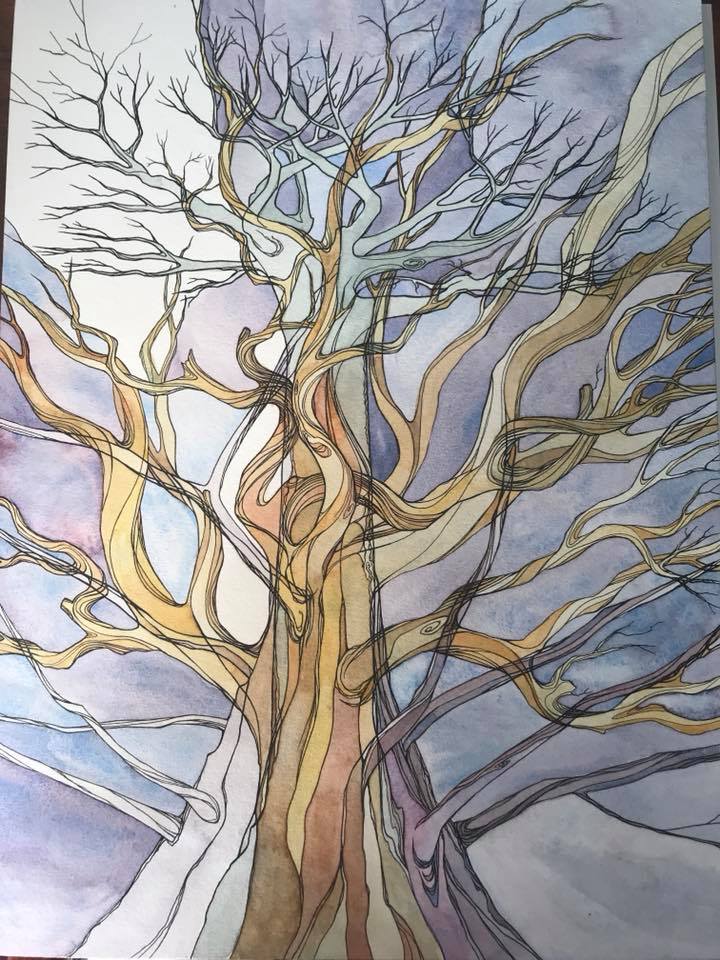

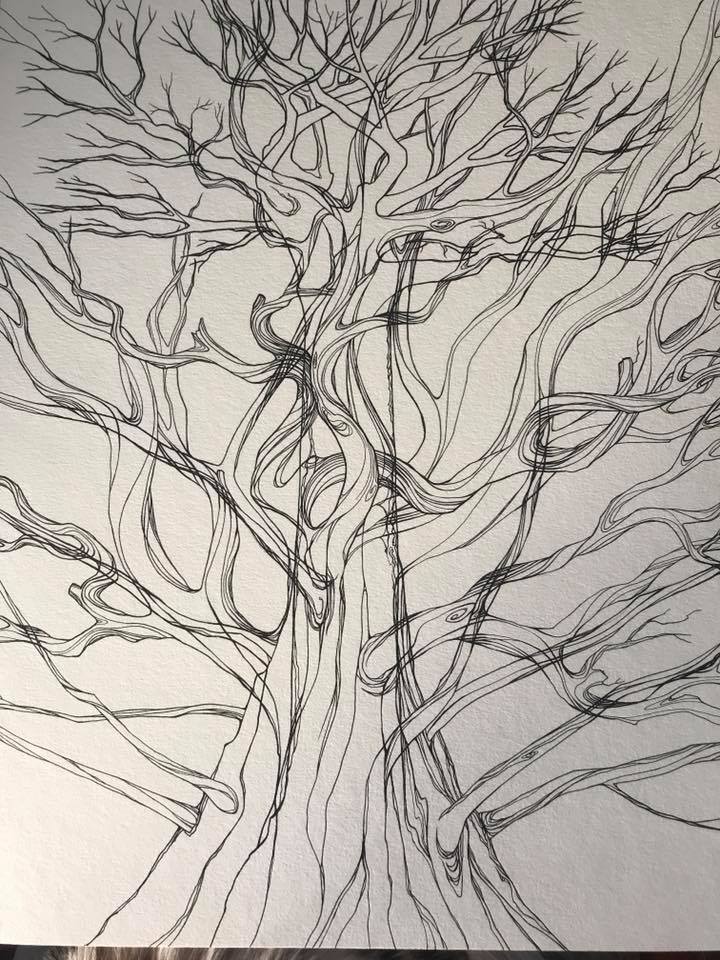

Maybe one of the things that distinguishes artists from everyone else is that we have the ability use our heartbreak, just like any other strong feeling, and make something beautiful out of it.

And by beautiful, I mean an experience of profound truth (or epiphany, or enlightenment, or whatever you want to call it) that can be shared—moment for moment—with others.

Heartbreak does not necessarily result in apathy and depression (the mind's mad dash for refuge from the external world).

No. Heartbreak can generate its own heat.

There, we can warm ourselves, and others.

We can use it to spark change.

We can burn things down with it.

We can illuminate the whole world with its light.

Anyway.

Maybe it's that strangers don't seem real to me. Only when I start to really know a person do their actions (no matter how horrible) begin to make sense. Without that, strangers just feel like the weather. They aren't moral or amoral, they are just natural phenomena.

Context alone allows me to build a bridge between myself and another person. I need it to read scientific studies just like I need it to read novels. That bridge can be made from the flimsiest of materials, too. Almost anything will do: a note, a personal story (even if it's a lie), a mistake. Any glimpse of the real person, underneath what they want the world to see, will do just fine.

And then, it's easy.

It's so easy it's kind of dangerous, actually. But usually it's worth the risk to keep on building, even if the bridge breaks, and I fall through. Because at least I fell on my way out, right? I didn't perish of loneliness and boredom, safe inside my own bedroom.

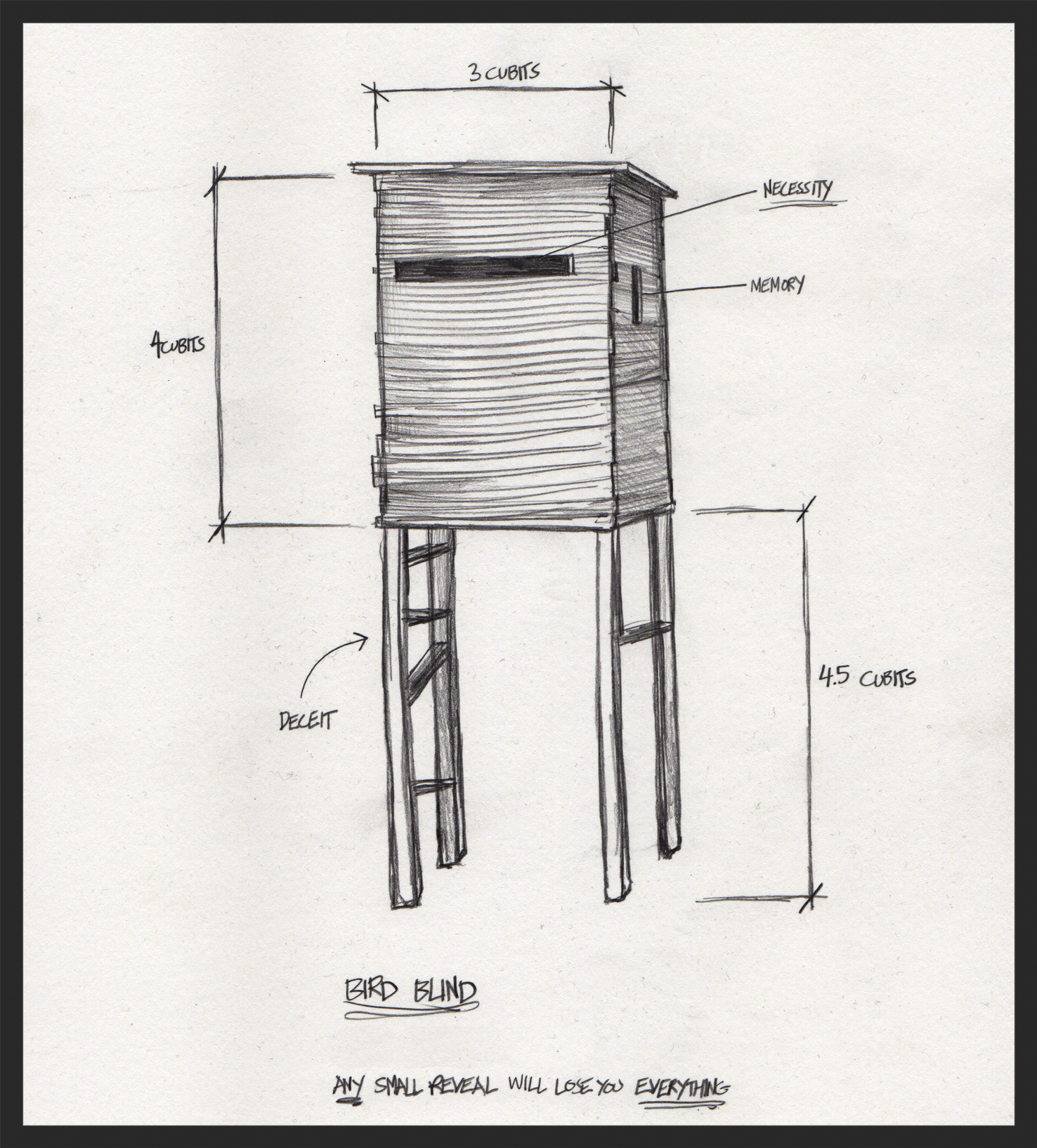

But here's the real kicker: there's also a way out from the inside.

Remember that part about the beautiful thing that can be shared? That's not a bridge that you build. It's not the effort we make to understand another person, it's a tunnel. Tunnels were there all along, but because they are underground, we don't see them. Tunnels are naturally dark. They lead deep inside ourselves.

If you were ever at the beach as a kid, maybe you made one of those tunnels in the sand where you started digging from one side, and another kid dug from the other side. The moment when your hands finally touch in the middle is always filled with joy and astonishment. And then you've got your tunnel. But it was the moment those two hands touched that was the important part, in the end.

Tunnels lead to other people, just like bridges do.

We do need to meet the world outside in the open too, on a bridge we built ourselves. We need to make contact with the world on purpose. Tunnels aren't a replacement for bridges, they're just an analogous solution that meets the demands of a very different landscape.

But really, what can compare to the experience of finding human companionship in the darkness of the tunnel?

It's like finding a lost golden ring, which you had long ago given up looking for, in the mud.

It's like finding an unmistakable description of yourself deep inside a tedious story written by an unknown author.

It's like discovering that you and the stranger sitting next to you on the bus had the exact same dream.

There is inevitably a feeling of fear: of invasion, distrust, even betrayal...at first. The world has suddenly tilted. What is this interloper doing here? Isn't there anything really unique about me?

You'd think it gets easier after the first time it happens, but it doesn't. It's a shock every time, and the experience isn't necessarily pleasant.

Pleasant or not, though, it's a miracle. There just isn't any other word for it.

So why aren't I talking more about social justice, and revolution, and capital-p People?

The truth is, I'm far too lucky to usefully participate in the larger conversation. I believe that my job is to listen (listen a LOT), to use what I learn from listening to guide my actions, to share the resources I can with those who need them, and to otherwise support those who are, by temperament or perseverance or some other quality I have failed to develop, fitted for revolution. But my own bridge-building skills simply do not extend that far, and it's good to know that about myself.

What I am good at is tunnels. I know how to share the experiences that make my life worthwhile with others. And it has extended far beyond my immediate sphere of influence, too. I can make tunnels that total strangers can find. Tunnels can change the world, too.

I'm telling the truth here, really I am.

You can go and just love your own experience of beauty—whatever makes the world make sense to you—and make your home inside it. There are tunnels there, in the dark, and you don't have to be alone, either. I promise.

And the best part is that nothing (except ourselves) can hurt us down there in the dark. Our fear only makes us lovelier. Hatred does not matter anymore. Rage fills the air with the music of a thousand hummingbirds, and our broken hearts catch fire, illuminating our beautiful faces.